May 22, 2023

Pages 308-314

Whole Number 22

THE STORY OF 25.2 THOMAS HUNTER SPARKS (1814-1863) Continued

by Charles H. Smith

In the March, 1958, issue of The Sparks Quarterly the events in the life of 25.2 Thomas Hunter Sparks, son of 25. Martin P. and Elizabeth (Whatley) Sparks, were related to the year 1861 when Thomas, with his family, left the comforts of his plantation in Cedar Valley and moved to Clark County, Arkansas, where he had purchased a tract of 2,240 acres.

The "Arkansas Dream" was doomed to failure. Adversity and sorrow first struck on August 16, 1863, when ten-year-old Carter Whatley Sparks died from some local malady. On a Sunday afternoon a fortnight after Carter was buried, his father and mother were walking over the property and stopped to admire an impressively wooded knoll, which prompted his father to remark, "Wife, when I die, I wish to be buried there." She replied: "But, husband, you are too young to contemplate death." He responded: "I am not too sure of that"; and they walked on. (Was it a premonition?) This was on September 6, 1863; one week later, on Sunday, September 13, at 10 P.M., Thomas Hunter Sparks died and was laid to rest in the grave with his son Carter, who had been his constant companion--not on the wooded knoll, but in the Bozeman Community Cemetery five miles from Arkadelphia, Arkansas.

On the day of his death, he dictated his last will, which reads as follows:

"In the name of God, Amen. I, Thomas H. Sparks, of the County of Clark and State of Arkansas, being of sound mind and memory and considering the uncertainty of this frail and transitory life, do therefore make and ordain, publish and declare this to be my last will and testament, that is to say:

"First, after all my lawful debts are paid and discharged, the residue of my estate, real and personal, I give, bequeath and dispose of as follows: To wit. To my beloved wife the tract of land upon which she is situated, embracing the whole tract of land which is on Boggy and McNeeley Creeks in the County of Clark and State of Arkansas, which the deed and certificate will show, embracing stock, household furniture, farming utensils contained on the place, also the slaves that I possess. My wife to hold and control according to circumstances that will best protect the interest of my estate now possessed by me, during her natural life or widowhood. After death or marriage, to be equally divided with the heirs of her body and at majority of my son Linton for him to have his equal share and all of my sons as they become of age to receive their equal shares. If either son shall decease before becoming of age his portion to be considered as the original estate. My two daughters, Sarah Jane and Eliz. Towns, whenever they shall marry, that their portion of my estate be settled upon them and their heirs. To my mother, a servant of her own choosing to wait on her during her life and $1000 annually from my death and at her death for her to dispose of it at her will with her grandchildren. I also will and bequeath to my wife and mother, $40,000 in Confederate money, $30,000 in notes on different persons. I also will and bequeath to my wife and mother certain tracts of land in Mississippi known as the Lost Lake Place, which the deed and oertifioate will show. I also ---?--- my stock and dividend in the Athens factory in Georgia amounting to $40,000. I also will and bequeath to my wife and mother my stock and dividend in the Georgia Railroad, $5,000 as the original stock and whatever there may be due on the same. I also will and bequeath to my wife and mother certain notes amounting to several thousand dollars in the hands of Col. Herbert Fielder. Also one note in the ---?--- of William Moore of $1250. Likewise I make, constitute and appoint my wife Ann Sparks and Michael Bozeman to be executors of my last will and testament, thereby revoking any former wills by me. In testimony whereof I have hereunto subscribed my name and annexed my seal this 13 September 1863.

[Signed] Thos. H. Sparks (Seal)

Test.

William Jones

J. R. Wilson

"It is understood my daughter Medora and my son James Martin are to have their portions out of my estate upon the appraisement as though they had an advancement already. Then they shall have out of my estate such portions as shall make them equal to my other children. The property hereby bequeathed to my daughter Medora is given to her and her children.

H. H. Coleman [Signed] Thos. H. Sparks

J. R. Wilson"

The will of Thomas Hunter Sparks, although made, witnessed, and executed in Clark County, Arkansas, is recorded in the court house in Athens, Georgia, also in the Floyd County Court House at Rome, Georgia. The explanation is that, in order that the estate might be settled, it was necessary to record the will in both places. A search in the court house in Clark County, Arkansas, by a member of the family disclosed blank pages left in the Book of Wills, the first page being headed: "Will of Thomas H. Sparks." However, the will was never recorded there, presumably due to a shortage of clerical help during the Civil War. It was first located in Will Book D, pages 188-205, in Athens, Clarke County, Georgia. The will itself, as can be seen, is relatively short, but there are six pages of legal appendanges. Ann Sparks, as one of the executors, provided bond in the amount of $60,000. James M. Sparks, her stepson, and R. P. Peeples, signed as securities on November 10, 1865, in Clark County, Arkansas. Since Martin P. Sparks, father of Thomas H. Sparks, had the middle name "Peeples," it would seem that R. P. Peeples was in some way connected with the family, but thus far he has not been identified.

Thus, Widow Ann Linton Sparks was left at the age of thirty-six with nine children of her own, the eldest sixteen and the youngest still at the breast, together with a stepson, James, and a stepdaughter, Medora, both of whom were married. Thomas H. Sparks died believing his family would be well provided for. He owned plantations, not only in Arkansas but in Mississippi, and land in Texas. However, due to sickness and occasional deaths, the slaves in Mississippi had been shifted to Arkansas and "Lost Lake" abandoned. He had invested $30,000 in Confederate Bonds and had $40,000 in Confederate cash, confident in the ultimate success of the Southern cause.

As a young widow, Ann Linton Sparks took over the management of the plantations in the midst of the Civil War. As the months passed, her burdens grew heavier. In April, 1864, a group of marauders of the Union Army, led by a Col. Kidd, arbitrarily commandeered 1,330 bushels of corn. They arrived at noon time, as dinner was being served, and, regardless of the absence of men and the hunger of the children, pirated the meal. On departing, they left a receipt for the corn, knowing that it was a worthless slip of paper. Such is the hypocricy of war. None was ever fought for a Godly cause.

The fall of the Confederacy ended the Arkansas dream. Ann Linton Sparks packed her requisite belongings and moved to Athens, Georgia, where she occupied a house owned by her older brother, Dr. John Linton (previously mentioned). Since baggage was not checked in those days, the owners were responsible for seeing that transfers were made from trains to boats and boats to trains. At Memphis, all trunks were put aboard the boat on the Arkansas side. One particular trunk impressed the stevedores as being unusually heavy and they were heard to comment to that effect. Arriving at the Memphis side, no check of the baggage was made. However, on reaching Athens, the "heavy trunk" was missing. It contained the "family silver." Although son Linton returned to Memphis to recover it, neither trunk nor any of its contents were found. Nor, to this day--regardless of its being initialed--has a piece been heard of. Of the "family silver," only that carried in a handbag, for feeding the children enroute to Athens, was saved.

The reason Widow Sparks decided to return to Athens was not only in order to live in a familiar environment, but, more important, in order that she could educate her children at local schools and the university. Sarah Jane was sent to a girls' school at Lagrange, Georgia, where she spent the closing months of the war. When Union troops entered the town, the girls were notified "The Yanks are coming." Having been instructed regarding their conduct and warned that they would doubtless be dispossossed of most or all of their belongings, they squeezed themselves into as many garments as possible and waited. Sarah Jane recalled "twenty" and "looking like a balloon." On arriving, the "Yankees evaluated the situation with circumspection," although conversing with the girls; one of whom presented Sarah Jane with a "ten dollar greenback," which she feared to accept or refuse. It was the first valuable money she had seen in many months. Fortunately, the troops were either of superior origin or under orders of superiors of gentility--the girls being accorded merited respect.

The war of shooting was over, but Reconstruction defiled the south. There was a revival of social life, however, in which the Sparks family participated. Although reduced in circumstances, Sarah Jane had two maids to dress and admire her, and to attend her, regardless of the hour, on her return from social affairs. Those were her halcyon days. Marriage and motherhood imposed obligations and responsibilities remote from those of a "Planter's Daughter"; but as wife and mother, she excelled--a model "worthy of all acceptation," just as in her halcyon days she was an exemplary and model daughter.

Before leaving Cedar Valley, the home furnishings, consisting of mahogany of "clawfoot" design from Maryland, a harpsicord, and less valuable articles had been sold locally, with the understanding that they could be reclaimed if wanted. In the middle 1890's, Charles Sankey Sparks, youngest son, with his wife Lee Ella, cruised the area in search of the ante-bellum furnishings. Aside from the harpsichord, nothing was found. It was purchased and sent to their home in Rome, Georgia, and is now the property of Mrs. Sarah Smith Henshall (only daughter of Sarah Jane and her husband, Hines M. Smith) now residing in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Although aged and crazed and missing many ivory tops for the keys, it is still a handsome instrument, an antique worthy of a place in any museum. Fortunately, Mrs. Henshall and her retired husband, George K. Henshall, Sr., are engaged in a work of restoration such as will revitalize the strains of a century ago.

The mother of Thomas Hunter Sparks, Elizabeth (Whatley) Sparks, became a member of her son's household following the death of Martin P. Sparks in 1837. She moved to Arkansas with the family, and, following the "fall of the Confederacy," moved, with her daughter-in-law and family, to Athens, Georgia. There she died on September 4, 1870, at the age of seventy-five years. Her body was returned to Cedar Valley and lies beside that of her husband. She failed to leave a will; at least none is on record. A much read and badly worn New Testament, published by the American Bible Society in New York in 1859, carries this presentation: "To Grandmother from her devoted Grand Daughter Medora, May 1st, 1862. - - Affection's Gift - - Her Children rise up and call her blessed." (The penmanship is excellent.)

|

| Photograph of Mrs. Ann Linton Sparks and child, believed to have been her youngest daughter, Annie Elizabeth Sparks |

(Handwritten Page) |

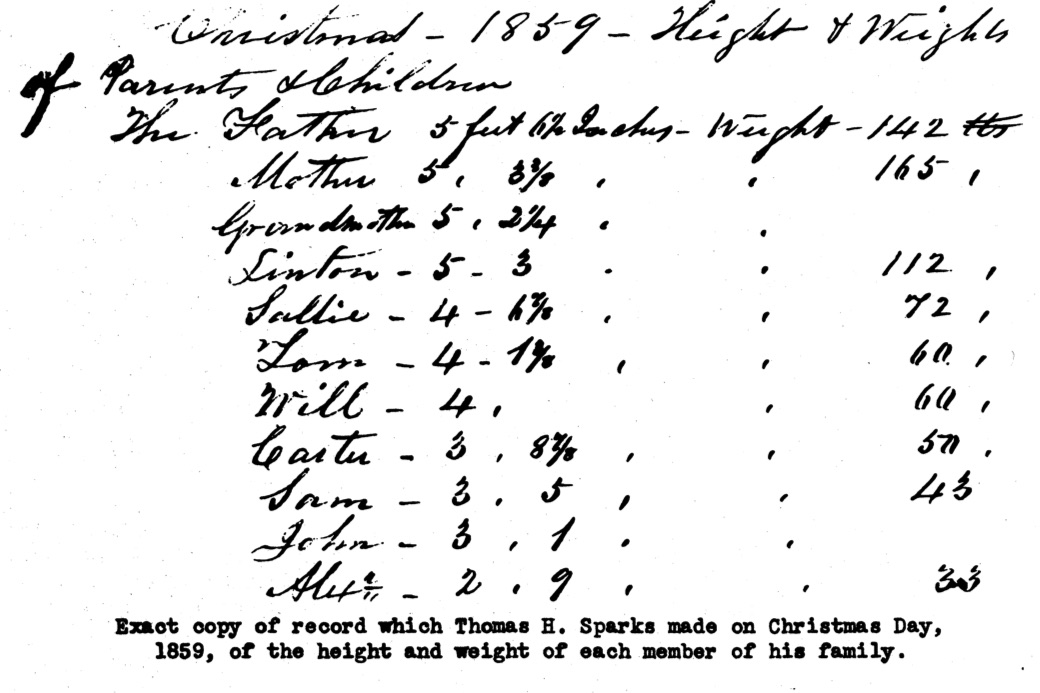

| Exact copy of record which Thomas H. Sparks made on Christmas Day, 1859, of the height and weight of each member of his family. |

My Grandmother, Ann (Linton) Sparks, seldom discussed the past, so, little could be learned about the every-day occurrences of her life as wife and widow. She did disclose that her son Sam was bitten by a copperhead while playing on a lumber pile, and son Alex. was kicked by a mule on her brother John's place in Athens, converting him to a friend of false teeth at an early age. Questioned about the loss of "Grandfather," Thomas H. Sparks, at the comparatively early age of forty-nine years, to which she seemed, outwardly, to have become entirely reconciled, she replied, in substance: "He died thinking the Confederacy would survive. Had he lived to be confronted with the vicissitudes of defeat, having had so much, I fear he would have found life difficult. It was the way of Providence." When Grandmother died, my father's tribute was: "She was the best woman I have ever known," a conviction shared by all who knew her. Before her death, she destroyed a drawer full of personal letters and effects considered "too intimate" for the curiosity of posterity. Of such was the gentility of her times. God bless her.

Daughter Sarah Jane recalled that on one occasion she was to accompany her father and mother on a visit. She was duly dressed, her clothes packed and in the carriage. For some childish reason, she was unhappy about her attire. Rufusing to be reconciled, she was left at home--her father's ruling. This incident illustrates the importance of rational parental austerity as recognized a century ago by Thomas H. Sparks, and so universally ignored today. (In this Scribe's case, "peachtree oil" and the "hickory stick" were unencumbered.)

Shortly after my advent, in Athens, Georgia, on June 15, 1872, my Grandmother Sparks purchased a home in Rome, Georgia, where my parents had settled--which home she shared with them for many years on a mutual expense basis. Later she purchased a larger and more pretentious home "across the street," into which we moved. In 1889, my Mother (Sarah Jane) purchased the "front yard" and built a modern home--the old house being modernized and occupied by "Grandma," her son Charles Sankey Sparks and his wife Lee Ella, until her death on May 3, 1895. She lies in the Sparks lot on Myrtle Hill at Rome, Georgia, with her three sons--John Veasey Sparks, Samuel Peeples Sparks, Charles Sankey Sparks, and the latter's wife, Lee Ella Sparks. Linton Sparks, eldest son of Thomas and Ann, and his wife, Sally Wimberly, are buried in Cave Spring, Georgia. (Uncle Linton is remembered with particular affection. He was a frequent visitor with Grandma in his homes at Etna, Priors Station, Cave Spring, and the "Tumlin Place," where I say my first and last flying squirrels and my only alternately-coupled black and red snake. Memory recalls how at Etna he gathered hickory nuts and sweet gum from the trees for the children, and how, when there, we occupied the front room, first floor right of the center hail; how in the mornings he slipped in and "lit the fire." The blowing, flames and striking of the old Seth Thomas clock are still music in my ears.) Thomas Sparks, Jr., died and was buried in Tyler, Texas. Alexander H. Sparks is buried in Neame, Louisiana. He was killed by a train. William D. Sparks and his wife, Annie (Wimberly) Sparks, are buried in Punta Gorda, Florida. Annie Elizabeth Sparks and her husband, David B. Hamilton, Jr., are buried on Myrtle Hill, Rome, Georgia. The parents of the writer, Sarah Jane Sparks and Hines Maguire Smith, are buried on Myrtle Hill, beside their second son, Linton Sparks Smith, and fifth son, "Little Hines." Medora Sparks, daughter of Mary Ann Linton, and her husband, Col. James Waddell, are buried in Marietta, Georgia. James Sparks, brother of Medora, and his wife, L. Virginia Blance, are buried in Cedartown, Georgia.

Among the writer's uncles, William Daniel Sparks was "a big brother." Following his return from Arkansas to Georgia, he attended local grade schools in Athens, matriculating at the University in 1871. There is no record of his being graduated. A recent disclosure is to the effect that he left Athens rather suddenly, following the disappearance of a negro soldier, a former slave, guilty of "pushing" the Athens girls off the sidewalk. If there is substance to this disclosure, he was not alone in the "disappearance." However, his resentment and courage can be vouched for in case of such a circumstance. He was fearless. My first recollection of him is as manager of the Etna Furnace Company's store at Etna, Georgia. It was while employed there that, on June 1, 1882, he married Miss Annie Elizabeth Wimberly. The author is the lone surviving witness of the event. Prior to the wedding, Grandmother Sparks went from Rome to Etna to rehabilitate a dilapidated employee's house on "Furnace Row." It was a two-story structure of rough boards, applied vertically and stripped for protection against the weather. The floors were of 12-inch planks, dresse'd on one side, but neither tongued nor grooved. The inside walls and ceilings were undressed. It was a sorry prospect--however, to Grandma, just another incident. Her versatility was limitless. The exterior was whitewashed--the inside walls and ceilings covered with cheese cloth, over which appropriate paper was applied. The floors were covered with matting, a practice universal in the south. Over the outside back stairs, upper landing, a grooved wheel was mounted, being equipped with a rope and bucket for elevating water, kindling wood, and coal to the second story. (This was a very wonderful contraption to me, and thrills me still. Only Grandma "could do so much with so little.") When finished, the transformation was that of a magician's wand.

Following the wedding at the home of the bride's mother at Prior Station, Georgia, Grandma and I joined the newlyweds on their wedding trip, in a "double buggy" with fringe hanging from the top, drawn by two horses, on their wedding trip of the long, long mile from Prior Station to Etna, where they crossed for the first time the threshold of their transformed abode. Of their honeymoon season, my memory recalls only their first Sunday night supper--cold fried chicken, cooked only as age knew how, cold biscuits, the usual side dishes, all cold. Being seated, our bride: "Willie, ask the blessing." Willie: "Lord, bless us and make us thankful for this cold snack. Amen." Irreverent? No, just a statement of fact. Nevertheless, consternation and, "Why! Willie!"

I do recall not spending the night with Joe Stilwell, son of the Furnace Superintendent, for the reason that he refused to close the door to his room on account of fear of being "hanted" by the cats he had killed. He died later from typhoid fever. That was seventy-five years ago, when pig iron was reduced from local ores with charcoal and furnaces belonged to independents. The woods were spotted with charcoal ovens, which devastated the forests. The "pig" was known as "hot blast" and was considered superior to coke iron, known as "cold blast," which has long since taken its place, combinations having absorbed or eliminated independent furnaces. Etna has been only a name for an ordinary lifetime. However, while independents were still in power, William D. Sparks left Etna to assume managership of the Bass Furnace Company's store at Rock Run, Alabama, where his success was immediate and stewardship long. When a New England cotton mill company built a modern mill in Georgia, he was induced to assume managership of their extensive store. It happened that the agent of the mill, ignorant of southern pride and practices and afflicted with a disagreeable superiority complex, was given to domineering outbursts, one of which he directed to Manager Sparks, whose resentment was mimediate, also his resignation, together with a warning that further indignities would exact physical measures. Subsequently, William D. Sparks became manager of a second mill nearby, which position he later relinquished on account of failing health. In time, he recovered sufficiently to accept other duties, finally establishing a business of his own in Chattanooga, Tennessee. When that venture was closed, he moved to Florida, where he and his wife Annie lived with their son, William Randolph Sparks, until their days were numbered. In Florida, he fished his life away. Always a lover of rod and gun, he was self-sufficient. When in his late eighties, he accompanied the writer to Morgan County, Georgia, who hoped he would be able to bring to light some of the 25. Martin Peeples Sparks background, but without success, due primarily to a temporary digestive upset which precluded physical as well as mental effort on his part. He was an individuality deserving of far greater values than were his lot. Providential justice will bless him and "his Annie." William D. Sparks died and was buried in Punta Gorda, Florida. His beloved wife died in a hospital at Arcadia, Florida, but is buried beside him. Thus endeth an inadequate appreciation of an uncle and aunt of enviable prestige.

In a future issue of The Sparks Quarterly will appear a record, as complete as the author is able to compile, of the descendants of 25.2 Thomas Hunter Sparks--to be contributed largely by the descendants themselves. For the material on Thomas H. Sparks and his father, 25. Martin P. Sparks, it has been necessary to rely upon memory, legend, and official records. The tragic destruction of family lore during the Civil War imposes constant problems on those who "careth from whence they came and whither they goeth." It is to those who "careth" that we submit this "story," fully recognizing its failure to do credit to the worthiness of the actors involved. Selah. Except for the past, there would be no present or future. Time and space would stand still.

(Note: Such Sparks, Whatley, Linton, Daniel, Smith, Maguire, Holt, Hutchins, Dixon, Noyos, Rawson, Reed, and other data as I have are subject to call without money and without price. One never knows where or when the "missing link" will turn up.

Address: Charles H. Smith

213 Dewey Street, Edgewood,

Pittsburgh 18, Pennsylvania.)

Editor Bidlack and the author wish to thank those who have contributed, both data and dollars. Among them:

Miss Lucy Linton, Athens, Georgia

Mr. Frank T. Sparks, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Mrs. Sallie Sparks McHenry, Ambridge, Pennsylvania

Mr. and Mrs. G. K. Henshall, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Miss Anne Mae Mims, Augusta, Georgia (Miss Mims is compiling a genealogy of the Whatley family.)

Miss Anne Hamilton, Rome, Georgia

Mrs. Annie L. Sparks Omberg, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

The family of the late Dr. John G. Herndon, Jr., for his invaluable contributions.

Mayor C. W. Bramlett, Marietta, Georgia, and Mrs. Alice W. Heck, of his staff

Mrs. Lucy Young Hawkins, Cedartown, Georgia

Mrs. Kirby Anderson, Madison, Georgia